A word of warning – Try to not overthink it.

Just saying the words “system” and contemplating the intention to impact the “system” can bring on a sense of overwhelm and confusion. “Systems thinking” can seem like a way of thinking that is often too academic with images of incomprehensible diagrams and jargon coming to mind. And so systems thinking stops before it begins. But it shouldn’t. Put systems thinking to work. Give it a practical purpose. Determine what needs to be understood, build a shared purpose with people, address what’s not working and amplify what is working.

Systems thinking and systems mapping supports a process of acting strategically utilising the finite resources that are available. Taking a systems perspective provides a different way to see and make sense of challenges. When working in community, working with social challenges, and working to innovate, people are often trying to figure out ‘what’s going on?’ When barriers seem invisible but un-moveable and the way forward isn’t obvious, systems can help the process of stepping back, looking at the big picture and attempting to see the situation differently. From there, it’s about working out how and where to intervene within the system in order to get results.

The ideas and stories captured here were shared by members of the Regional Innovator’s Network (RIN) during a peer learning session on 2 October 2018.

Quick Summary

What does it mean

- Defining ‘systems’: a system is a way to support people in an organised way

- Taking a systems perspective helps people seeking change to identify where to intervene

What helps

- Scoping and framing an initiative from a systems perspective

- Mapping systems – to make sense of what’s happening and see opportunities

- Influencing the system – at each phase, through leverage points and by engaging people

What hinders

- Not taking a systems view

- Overthinking it

- Systems mapping for the sake of systems mapping

What does it mean?

Defining ‘systems’: a system is a way to support people in an organised way

The purpose of a system is to deliver some type of service to society, in some sort of organised and coordinated way. Systems are a part of everyday life – for example the educational system, the roads system, the emergency response system and the judicial system. When systems work well they make life easier and even better. That’s generally what they’re intended to do. But they can also be environments that lead to dysfunctional, strange behaviours and even unintended harm.

People create systems, but once created systems are hard to control and they don’t always behave as intended. Systems are often described by their many paradoxes. For instance:

- You can’t touch systems, but they definitely exist

- If you chop the system into little parts, you do not have the whole (one teacher does not make an education system)

- When a part changes, the whole changes

- A system has its own logic and rules — it’s own identity and behaviours

- The whole can behave in ways no one ever intended

- When you try to change things you may get unexpected results!

Source: Ackoff, Russell L. Ackoff’s Best. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

Systems as ‘things’ can be really hard to see because, surprisingly, if you’re in the system then you are the system. Kevin Slavin gave us an example of this when he pointed out, “you’re not stuck in traffic, you are traffic”! All people are actors in systems, impacting other actors in the system, and this often goes unnoticed as the system is often perceived as something separate from the individual. In reality, however, everything you do every day, every choice we make, either reinforces the system or shifts it.

Source: Slavin, Kevin. “Design as Participation.” Journal of Design and Science, no. 1 (2016). https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/design-as-participation

If you’re looking to learn more about systems, read up on the following:

- Systems thinking: the original discipline for studying systems, which gave us causal-loop diagrams and flow maps

- Systems theories: complexity theory, organisational theory, complex adaptive systems, evolutionary theory, and more!

- Systemic design: an emerging discipline that could be described as design-based innovation methods meet strategy and systems thinking

Taking a systems perspective helps people seeking change to identify where to intervene

People seeking to create change often need to shift or build a system for that change to occur. Systems thinking helps people to ‘see’ the system and identify where to intervene by leveraging the key points (including people) in the system in order to enable change. Intervening with the system can take many forms. An intervention can be a new service, a new role, a technology solution, a media campaign, etc. No matter what the intervention, creating change always involves influencing people — but which people? And how?

A few key activities can help a team take a systems perspective:

- Scoping and framing the initiative – from a systems perspective

- Mapping systems – to make sense of what’s happening and see opportunities

- Influencing the system – at each phase, through leverage points and by engaging people

These activities are described below. You can do any of these activities with a working group as well as with stakeholders, as long as it is presented in a way that it makes sense for them.

The above information is discussed in greater detail by Michelle in the video below.

What helps?

Scoping and framing an initiative from a systems perspective

At the beginning of an initiative, there is typically a phase of scoping and framing at the start. Framing is the process of defining the problem or opportunity that is being addressed. We can define a problem or opportunity in many different ways and at many different levels, and so the lens – or frame – you take is critical is you are to be productive in your approach. Taking a systems perspective during this process is part of making sure that everyone involved is on the same page. Here are a couple of systems activities to use during framing:

- Funnel of scope — the funnel of scope is a funnel with a few different levels: too high, too low, in the middle – ‘just right’. Kind of like the Goldilocks and the Three Bears story… To use this tool, write out a number of different ways to frame your initiative. Are some aspects too high in the funnel — too abstract and broad for the team to be able to make a difference? Are some too low in the funnel — too small to make a difference? Which one(s) are just right — tangible enough for the team to act and also make a difference?

- Drawing the system boundaries — within a system there can be many, many systems — like nested Russian dolls. For instance, within the educational system there are districts, schools and classrooms — and each of these can be considered to be a system. Additionally, many different systems can overlap. If we are trying to support young people, are we talking about community activity, education, sports, services or the justice system — or all of the above? In the scope of your initiative, list the different systems that may be involved. Draw a circle to represent the boundaries of your initiative and decide which systems fall inside and outside the scope.

Mapping systems – to make sense of what’s happening and see opportunities

Visual mapping is used as a starting point to get a picture of a system. Systems are intangible and complex. How people think about a system differs from person to person – in a workshop of 20 people there may be 20 different mental models of a system. And so we use visual mapping to develop a shared picture of the system we are working with.

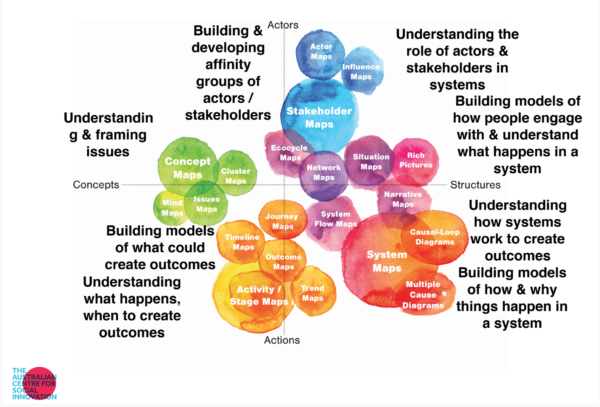

There are many different types of systems maps. When the term ‘system map’ is used, causal-loop diagrams and flow maps may come to mind. But these are only two types of system maps. The diagram below presents a number of types of systems maps, and the purpose of these maps. There are also several examples in the ‘Understanding and leveraging systems’ guide, which is available via link at the bottom of this page.

Source: Ingrid Burkett

When mapping a system, choose the type of map that fits the objectives.

Do you need to:

- Explain the different components of a system?

- Map the various actors, and how they’re connected?

- Use an easy way to compare mental models of a system?

- Identify the various stakeholders of an initiative?

- Understand the experiences of a user through the system?

- Explain how a system works?

To help you choose the right type of systems map, think about the audience. Is the map for the team, and the team’s learning process? Is the map for stakeholders? Is it for a broader audience that you may never meet in person? What information do they need to know? Sifting through these questions will help a team get the most out of systems mapping and keep it practical.

Systems maps can provide surprising insight. The very process of making a systems map can be informative. Once a system map has been created, information gained in discovery can be linked to the map to flesh out and iterate the map. An analysis of the map can provide fresh insight into how the system works as well as pain points, gaps, successes and opportunities. In other words, system maps can help people identify where to intervene in order to change a system, and can provide clues as to what types of interventions might work as well. Once a system map has been created, if it is not presented and discussed in person, it usually requires labelling and a clear written explanation of the intention and information that can be understood by reading the map. It can also be helpful to include call outs that point out the key data points, insights and implications of this information.

In the video below, the Network discusses an example of where a simple map may be far more effective than a complex and detailed map for a particular audience. Remember, sometimes granular detail is important and sometimes ultra-simplicity is the most effective.

Influencing the system – at each phase, through leverage points and by engaging people

Mapping and analysing the system makes it easier to see where you could take strategic action in a system. Below are a few ways to put that into action, to go about influencing the system.

- Systems thinking at every stage of an initiative, e.g. a co-design process.

Consider the systems perspective at each stage of an initiative. In the project set-up phases, stakeholder mapping and setting system boundaries is important, as discussed above in scoping and framing initiatives. During discovery, asking questions and seeking information from different levels and parts of the system can help to identify where a conflict in perspectives is creating issues. This reveals where the system is working against itself.

In the design phase, developing solutions for different parts or levels of the system can ensure that conflicts, barriers, gaps and opportunities are addressed holistically. As mentioned, the various parts of a system are interdependent. Changing one part may not make a difference, but changing a few interdependent parts can shift a system. During testing getting feedback from different parts and levels of the system can validate the potential for results, and it can also reveal other barriers, gaps and opportunities in the system. In the final phase of spreading, taking a systems view will help anticipate what is needed for changes to be successful at scale.

It has been argued the design process itself is an intervention because it can lead to changes in a system, particularly in mindsets and paradigms. If the co-design process is viewed as part of a change process, as an intervention itself, what else can be done along the way to influence change?

- Examining the potential for change at leverage points

Leading systems thinker Donella Meadows identified leverage points in systems that can be acted upon in order to influence change. Her argument is essentially that some types of interventions within a system will have more effect on the system than others. Meadows names nine leverage points, which are ranked by the extent to which changes in these aspects of the system have the power to change the system as a whole. The leverage points are as follows, listed from least influential to most influential with examples to illustrate from the school system:

- Constants, parameters, numbers – e.g. educational testing standards shape expectations across the system

- Regulating negative feedback loops – e.g. changing school suspension so that it doesn’t make it harder for those who are behind to catch up and so that getting suspended is not the goal of some of the most disengaged young people

- Driving positive feedback loops – e.g. how participation in sports can help create positive self-esteem

- Material flows and nodes of material intersection – e.g. equal supply of materials, textbooks and technologies to all schools

- Information flows – e.g. how information and opportunities for teacher development is shared across the district

- The rules of the system (incentives, punishments, constraints) – e.g. weapons and drugs are not allowed on school property and punishments having consequence in the judicial system

- The distribution of power over the rules of the system – e.g. what decisions teachers can and cannot make within a classroom

- The goals of the system – e.g. for all students to score as high as possible on standardised tests

- The mindset or paradigm out of which system arises — its goals, power structure, rules, its culture, e.g. the premise of equal access for all to education, the standardisation of curriculum, and a model of schooling based on Western approaches to education

- Engaging people for systems change

Change really comes down to people. Change doesn’t happen without people, and sometimes it requires certain people. People help to mobilise and influence others. Some people are able to unlock access to other people and resources. Some people are required to authorise activity and provide permission.

Taking a systems view can help identify who to engage across the system. From there, it is a question of when and how best to engage someone. Some people may need to be engaged throughout the entire process, others may need to be engaged only for specific phases. In some cases, taking a formal route is the most appropriate way to engage people across the system. In other cases, taking a formal route can be the exact opposite of what is needed — ineffective, counterproductive, antagonistic. In these cases, and in most cases really (even the formal route), relationships come first.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people often stress the extent to which relationships come first. Initiatives may need to go slowly at the start – more slowly than budgets and expectations tend to factor in – in order to build the trust and relationships needed to move forward at all. It’s not just a matter of going slow at the beginning in order to go fast later. Sometimes we need to start with relationships – without expecting anything. The power of taking time, building relationships, and moving forward together with people should not be underestimated — after all, it is people who create change and system cannot be changed by one individual acting alone.

Engaging people through the co-design process is discussed further in Capability 2.4: Bringing others along the journey. The link is at the bottom of this page.

In the video below, Michelle talks through the points outlined above.

What hinders

Not taking a systems view

The purpose of systems thinking is to prevent a short-sighted view. There are so many stories of great work, so why don’t things change? Individuals can create an incredible impact on a community. But what happens when they’re not there anymore? Taking a systems view and working toward systemic change can create a difference for the long term.

Overthinking it

Just saying the words “systems thinking” gives a pause. Images of incomprehensible diagrams come to mind. Even less comprehensible jargon is often involved. And so systems thinking stops before it begins. But it shouldn’t. Put systems thinking to work. Give it a practical purpose. Determine what needs to be understood, build a shared purpose with people, address what’s not working and amplify what is working.

Systems mapping for the sake of systems mapping

It’s easy to get lost in the details of a system. It’s understandable to want the help of a visual tool. But when creating systems maps stay focused on what needs to be learned, what needs to be seen, and the shared understanding that is required to move forward or identify more productive actions. Putting all the detail in – if it’s needed – can come later. Making it pretty can come later. Start sketching and keep coming back to the purpose of systems mapping, let that guide the way.

Frameworks and Resources:

- Understanding and leveraging systems presentation

- Types of system maps

- Example – Drawing boundaries around scope

- Example – Working with the funnel of scope

Related Capabilities:

- Bringing others along the journey

- Partnerships…